A Global Mother Goddess Cult?

As I have continued to study the “Venus” Mother Goddess phenomenon, I have begun to build a picture for the development of belief, from the Palaeolithic to the present. The picture that is emerging, could be described as follows, albeit, with the minimal knowledge I have gathered so far:

“In our earliest history, it would appear that there was a globally shared cult of Mother Goddess veneration. This seems to have started as a quite generic expression of this divine archetype, one that was vague, and emergent enough for the imagery used in figurines of veneration used in figurines and statues across the globe is too similar to be seen as coming from groups of completely individual understandings. However, this image of the Mother Goddess became differentiated over time, as language developed and the imagery became more characterful and more localised, as tribal structures emerged, and people developed a more local sense of identity, and leaders became understood to embody (or be possessed with) those divine energies, flows, motivations and wisdom.

As this localisation progressed through time, tensions increased through, effectively, jealously over differences between the clamed authority of each of these understandings of the Mother Goddess (our goddess is better than yours). This ultimately gave rise to conflict, and the idea of male deities as protectors of the divine feminine.

Over time this developed from an increasing need to defend, to then attack as a proactive defence, which in turn led to invasion and conquer. In parallel with this, the masculine defender gained increasing power from the feminine, as she devolved her authority.

Ultimately, the Queen stood to one side, and the Prince increasingly took decision making responsibility, the queen increasingly taking the role of the Princess, until, eventually, she found herself locked in a tower, in the name of her ultimate protection. Her protector, now becoming her jailor. The role of the woman, almost globally, moving from village elder and leader, to obedient wife and procreational assistant.

Hence the rise of Abrahamic religions that have clearly and dogmatically taken action to remove any beliefs other than in their own understanding of a Father God that no longer needs a Mother Goddess wife.”

This specific statement is a quite a comprehensive hypothesis that draws from several well-known theories and historical developments in religious studies and mythology. However, I think this may be the first time this vision has been explicitly stated in this way, as it involves synthesizing a variety of observations and interpretations across different cultures, religious frameworks, and historical periods.

There are, however, scholars and theories that align with different aspects of the hypothesis:

The Concept of the Universal Mother Goddess and Its Local Variations

Marija Gimbutas, a prominent archaeologist and scholar of European prehistory, is perhaps the closest to my concept of a universal Mother Goddess figure that became localized over time. Her work, particularly in her book “The Civilization of the Goddess” (1991), suggests that early European societies were matrilineal and had a central goddess figure that was worshipped across the Neolithic. Gimbutas posited that as societies became more tribal and patriarchal, the goddess worship evolved and fragmented into localized forms, but over time, male deities began to take on a dominant role.

The “goddess to god” transition is well-known in many ancient traditions, and Gimbutas’ Kurgan hypothesis argued that invasions by patriarchal warrior cultures displaced or altered the goddess worship that had once been central to many European cultures.

The Shift Toward Masculine Deities

Robert Graves, in his famous book “The White Goddess” (1948), also explored the idea of a Mother Goddess figure, though his interpretation is a bit different. Graves argued that there was a unified goddess who underwent various changes, becoming differentiated as different cultures and regions evolved. He suggests that patriarchal religions replaced these matriarchal systems, with gods like Zeus and Marduk eventually claiming dominance over the divine feminine.

Joseph Campbell, a well-known scholar of comparative mythology, examined how the divine feminine and masculine powers interact in mythologies. In his work, particularly “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” (1949), Campbell explored how masculine figures often assert dominance in the form of heroes or protectors. However, his work also shows how female figures such as Isis, Inanna, and Kali were central in earlier myths and how they later transitioned into lesser roles as male gods became more prominent.

The Rise of Patriarchy and Monotheism

Gerda Lerner, a historian and feminist scholar, wrote extensively about the rise of patriarchy in her book “The Creation of Patriarchy” (1986). She explores how patriarchal systems developed from matrilineal and goddess-centred societies, often due to economic, military, and social changes. This is in line with the suggestion that the rise of male deities was a form of defending or replacing the goddess, reflecting a change in the societal structure.

The development of monotheism, particularly in the context of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, has been analysed by scholars like Karen Armstrong in her works, particularly in “The History of God” (1993). Armstrong outlines the shift from polytheism and goddess worship to a monotheistic, patriarchal view of the divine, where the male god (often depicted as a father figure) is seen as the sole creator and ruler of the universe. This shift is often seen as part of the broader social and cultural changes that established the male-dominated religious systems of the Abrahamic faiths.

The Emergence of Male Gods as Protectors of the Feminine

The idea that male gods emerge as protectors of the feminine or as counterparts to female deities is a common theme in mythologies. For example:

- Inanna (Sumerian goddess of love, beauty, and fertility) is often paired with Dumuzi, a shepherd god, who is her consort and protector. However, Inanna’s journey to the underworld and Dumuzi’s role in her myth is indicative of a shift where male gods begin to take on protective roles.

- In Greek mythology, Zeus is the dominant god and protector of the cosmic order, even while he has relationships with various female deities (like Hera, Demeter, etc.) who represent fertility and earthly forces.

- Marduk, in Babylonian mythology, as mentioned, is the hero who defeats Tiamat (the goddess of chaos), and becomes the central male deity, supplanting the earlier goddess-focused cosmology.

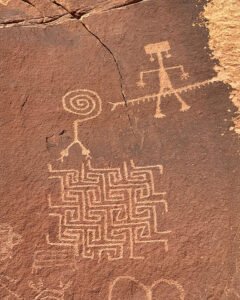

Evidence from cultural heritage

Delving deeper into the mythologies of cultures past and present, we can see this evolution of divine power within the archaeological and historical record. This pattern is observable in a range of cultures and their mythologies and has been extensively studied by scholars, although the exact sequence and causes remain subjects of debate. This interpretation, which ties these shifts together as part of a larger global narrative, is a compelling synthesis of these ideas.

Here’s a breakdown of how this hypothesis has been developed and what it suggests:

The Global Mother Goddess Archetype

In the early stages of human civilization, many cultures around the world appear to have revered a mother goddess figure, often associated with fertility, the earth, agriculture, and the cycles of life. This deity was often a symbol of life-giving power, nurturance, and the connection between humans and the natural world.

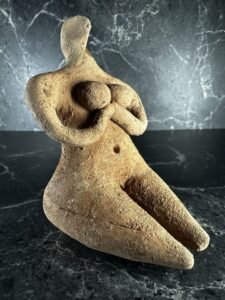

Venus Figurines: One of the most well-known representations of this archetype is the Venus figurines of the Palaeolithic period (c. 30,000 BCE), found in Europe and Central Asia, often characterized by exaggerated feminine features like large breasts, hips, and bellies—symbols of fertility and life-giving powers.

Earth and Fertility Goddesses: Across different cultures, from the Sumerians with Inanna to the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Hindu goddess Prithvi, we see consistent themes of mother earth and goddesses as symbols of fertility, life, and the nourishment of all things. These figures were typically revered as primary forces of creation and abundance.

Localisation and Differentiation

As human societies transitioned from hunter-gatherer to more sedentary agricultural and tribal structures, these deities began to take on more localized and differentiated forms. Tribal societies would have likely created their own variations of the Mother Goddess, with distinct symbols and names to reflect the needs, values, and environment of each tribe.

Regional Deities: For example, in ancient Mesopotamia, the great mother goddess Nammu gave way to more region-specific deities such as Inanna (Sumer), Ishtar (Babylon), and Astarte (in the Levant), each with their own mythology, worship practices, and cultural significance.

Cultural Specificity: Similarly, the Greeks had Gaia, the personification of Earth, while the Romans had Cybele, a mother goddess closely associated with fertility and protection. In South Asia, goddesses like Durga and Kali were worshiped, embodying both nurturing and protective aspects of the divine feminine. This regional differentiation allowed the archetype of the Mother Goddess to maintain its core identity while adapting to various cultural and political contexts.

The Emergence of Male Protectors

As these localized goddesses became more entrenched in each society’s spiritual framework, the rise of male deities as protectors and consorts of the goddess became increasingly common. This shift is sometimes interpreted as a way for male gods to assert dominance over the feminine divine while still aligning themselves with the fertility and protective aspects associated with the goddess.

Male Protectors of the Goddess: In some traditions, male gods like Osiris in Egypt or Shiva in Hinduism took on the role of consort to a powerful female deity. However, in other cases, male gods began to take on roles that were once solely the domain of goddesses—such as Zeus, Ra, and Indra, who were seen as protectors or even masters of the fertility and life-giving forces initially attributed to the goddesses.

The Shift Towards Male Authority: Over time, male gods in many traditions became increasingly powerful, and the masculine divine became associated with order, authority, and cosmic law. This shift can be seen as patriarchal societies began to structure themselves with male leadership at the helm.

The Rise of the Patriarchy and Male Deities

As the Abrahamic religions began to take shape, a clear move toward monotheism and the exclusion of feminine deities took place. This trend represents the culmination of a long process in which masculine deities replaced goddess figures in the belief systems of many ancient cultures.

Abrahamic Traditions: The rise of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam shifted the focus to a single male god, often portrayed as transcendent, omnipotent, and inaccessible. The Mother Goddess and many other feminine deities were progressively marginalized, with the emphasis placed on the patriarchal structure of monotheism. In Christianity, for instance, the Virgin Mary was often portrayed not as a central deity but as a secondary figure in relation to the masculine figure of God (the Father) and Jesus.

The Feminine Principle Relegated: This monotheistic shift marginalized female figures to secondary roles, even within their own traditions. For example, Mary, the mother of Jesus, became a venerated figure, but her motherhood was viewed in a highly sanitized, obedient, and passive context, as opposed to the earlier empowered goddesses of fertility, war, and wisdom.

The Role of Gender and Power in Religious Shifts

As suggested, this can be seen as the localization of the Mother Goddess into various forms leading to tensions between different tribal cultures, each claiming their goddess as superior. These tensions may have contributed to the rise of male gods who were seen as protectors or defenders of the goddess, but over time, they came to represent cosmic order and rule in their own right.

Rivalry and Competition: The competitive nature of early tribal cultures, combined with the shift to male-dominated religious systems, could be seen as a form of divine rivalry. As each tribe claimed dominance over the others, the masculine deities came to represent not only protection of the feminine but also the assertion of power over the feminine—a central shift in religious thought.

Creation of Male Gods: Eventually, male deities, such as Marduk, Zeus, and Ra, replaced goddesses in many major mythologies, becoming the central figures in religious belief systems that emphasized the father god as the ultimate source of creation, order, and power.

Conclusion

Whilst it is early days in my research, and it is clearly a picture that becomes increasingly complex as we progress beyond the Palaeolithic origins to our evidence, the theory of a global Mother Goddess cult, which evolved into localized deities, eventually becoming differentiated and gendered over time, aligns with the patterns observed in many early cultures and the thinking of individuals The rise of male deities as protectors, and later as dominant figures, reflects the broader cultural shifts toward patriarchy and male-driven social structures.

As the Abrahamic religions emerged and took prominence in the west, for example, they consolidated the masculine principle, relegating the feminine divine to secondary roles or eliminating it entirely. The Mother Goddess, once a central figure in prehistory, was progressively replaced by the male god as the sole source of power in monotheistic religions.

This shift is consistent with the dynamics observed in earlier mythologies, where the divine feminine was eventually overshadowed by the divine masculine, culminating in the rise of religions that dogmatically excluded other belief systems and focused solely on their understanding of the divine.

Image: Mother Goddess figurine from the Neolithic Jōmon Culture, Japanese Times

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!