Jomno Dogū figurines the most remarkable products of Japans Jomon Period Japan Times

The Jōmon culture of Japan and the Mother Goddess

The Jōmon culture is one of the oldest and most significant prehistoric cultures in Japan, known for its distinctive pottery, early agricultural practices, and complex social structures. The term “Jōmon” refers to the cord-marked pottery that the culture produced, which became a hallmark of their society.

The Jōmon period lasted from around 14,000 BCE to 300 BCE, and it is divided into different phases:

- Early Jōmon (14,000 – 10,000 BCE)

- Middle Jōmon (10,000 – 7,000 BCE)

- Late Jōmon (7,000 – 4,000 BCE)

- Final Jōmon (4,000 – 2,000 BCE)

- Earliest Yayoi (2,000 – 300 BCE)

This final period marks the transition into the Yayoi period, where the introduction of wet rice agriculture is thought to have occurred, and the Jōmon culture began to blend with other influences.

The Jōmon are most famous for their pottery, which is among the oldest in the world. The term “Jōmon” itself comes from the Japanese words “jō” (cord) and “mon” (pattern), referring to the distinct rope-like impressions found on the surface of the pottery. Jōmon pottery included a wide variety of shapes and sizes, from functional vessels to decorative and ritualistic pieces, and it is believed to have been used for cooking, storage, and ceremonial purposes.

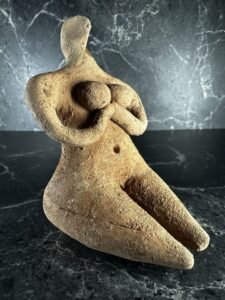

There were ceremonial figurines such as the Dogū, which are small humanoid figures with exaggerated features. These figures are thought to have had a spiritual or ritual significance, possibly representing fertility or ancestral spirits.

Jōmon Lifestyle

The Jōmon people were primarily hunter-gatherers, though they also began developing early forms of agriculture, especially in the later phases of the culture. They hunted deer, boar, and bears, fished, and gathered nuts, berries, and other wild foods. In the later stages of the culture, they began cultivating wild plants and crops, possibly including early forms of rice and root vegetables. There is evidence that the Jōmon people lived in semi-permanent settlements, building pit dwellings (large, often sunken houses with thatched roofs) and created community-based structures.

The Jōmon had a complex spiritual life, with beliefs related to nature spirits, ancestors, and possibly shamanistic practices.

Jōmon Figurine Japan Final Jōmon period ca. 1000-300 BCE

Jōmon Art and Culture

Their art, including figurines and the designs on pottery, suggests a deep connection to fertility and the natural world. The use of animal motifs, such as bear and deer, is common in their art, pointing to the spiritual importance of these creatures. There is some evidence of ancestor worship or veneration, with grave goods and ceremonial objects found in burial sites.

The Jōmon culture had a reasonably complex social structure, with different groups performing specific roles in society. Evidence of trade networks across the Japanese islands indicates that the Jōmon were not isolated, and there was exchange of goods and ideas between different regions.

The society seems to have been more egalitarian than other contemporary societies, with shared resources and a lack of evidence for rigid class systems, at least in the early stages of the culture.

Jōmon people constructed pit dwellings (sunken homes), which were dug into the ground to provide insulation from the cold. These structures were made of wood and thatch, with a central hearth. Over time, larger and more elaborate dwellings were built, suggesting that Jōmon communities began to develop more permanent settlements. The stone circles and other ritual sites found at certain Jōmon sites are indicative of their religious practices, possibly for community gatherings, ceremonies, or astronomical observations.

The end of the Jōmon period coincided with the introduction of wet-rice agriculture in Japan, marking the beginning of the Yayoi period. This shift towards agriculture brought about significant cultural changes, including the development of iron tools, social stratification, and new forms of architecture. The decline of the Jōmon culture also reflects the influence of new technologies and ways of life from the mainland (such as from the Korean Peninsula or China), marking the transition from a hunter-gatherer society to a settled agricultural one.

The Jōmon culture is regarded as a significant foundation of Japanese culture. Many of the values associated with the culture—such as nature reverence, spiritual connection to the land, and a respect for ancestors—are reflected in Shinto and Japanese mythology. The earth-centred spirituality of the Jōmon can still be seen in the rituals and practices that continue to shape Japan today.

The transition from the Jōmon to the Yayoi period is considered a pivotal moment in Japanese history, as it marks the shift towards the complex societies and advanced technologies that defined later Japanese civilization.

Venus figurines

The figurines of the Jōmon culture include some that bear strong resemblances to the mother goddess archetype found in various ancient cultures. These figurines, often referred to as “Jōmon Venus” or “Jōmon goddesses”, share several key characteristics with the Palaeolithic and later Venus figurines, such as exaggerated female features (large breasts, wide hips, and rounded bodies), which symbolize fertility and life-giving forces and have been found in a widespread distribution across Europe and in parts of Africa.

The Jōmon culture appears to have had a profound connection to female deities, much like many early agricultural societies that centred around fertility and the earth as life-sustaining forces.

While these figurines are not typically considered to represent the same goddess archetypes seen in Sumerian, Indus Valley, or European traditions, there are striking similarities that hint at a universal connection to the divine feminine across disparate cultures. This connection is grounded in the idea of life, fertility, and nature’s cycles, themes that are universally present in early human spirituality.

Jōmon Culture and the Mother Goddess Connection

Jōmon figurines, particularly the “Venus figurines” or “goddesses”, date back to the early Jōmon period (c. 14,000–4,000 BCE), and many of these small ceramic figures were likely used in rituals or as symbols of fertility. Some of these figurines also have facial features, but the focus is often on the female form, emphasizing the fertility and the nurturing aspects of the feminine. These figurines can be found across Japan, with a particularly high concentration on the northern and eastern regions.

Shinto and Its Connection to Jōmon Beliefs

Shinto, as the indigenous religion of Japan, holds the creation myths of Japan at its core, with goddesses and natural spirits playing a central role in its pantheon. The story of Izanagi and Izanami, the divine couple who gave birth to the islands of Japan, and the goddess Amaterasu, the sun goddess, are examples of feminine figures playing powerful roles in Shinto cosmology. While Shinto does not directly trace its origins to the Jōmon period, the reverence for nature, fertility, and the earth seen in Shinto is believed to have roots in the animistic and goddess-centred spiritual practices of the Jōmon culture.

Goddess Worship and Nature

The goddess symbolism seen in Jōmon figurines can be seen as part of a broader pattern of early human societies venerating female deities tied to life, fertility, and creation. These ideas were central to agriculture and the survival of early communities. The earth goddess or mother goddess was often associated with the nurturing of crops, animals, and families, reinforcing the idea of the feminine as being the giver of life and sustenance.

The Influence of Shinto

Although the goddess symbolism is prominent in the Jōmon culture, it’s worth noting that there is also evidence of male deities or gender duality in later periods of Japanese religious history. The transition from goddess-centred religious practices to the Shinto creation myths, which include both masculine and feminine deities (e.g., Izanagi and Izanami), marks the shift toward a more balanced view of divine gender in the creation and order of the world.

Shinto refers to the creation of Japan by the gods Izanagi and Izanami, which represents a shift from the matrilineal beliefs of earlier societies to a more patriarchal structure, where the male deities are more prominent in the myths. However, the reverence for nature, earth, and fertility remains a core component of Shinto, reflecting the Jōmon culture’s focus on these elements.

The Jōmon figurines, with their emphasis on the female form, can be seen as part of a broader spiritual and symbolic tradition that links early societies’ reverence for the divine feminine. These figures symbolize the nurturing, life-giving aspects of the Mother Goddess, which were important across many cultures, especially in the Neolithic period.

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!