The Vinca culture, (also known as the Vinča culture or Tordos-Vinca culture) was a Neolithic culture that flourished in the Balkans between approximately 5700 BCE and 4500 BCE. It is one of the earliest and most influential cultures in south-eastern Europe during the Neolithic period, known for its advanced agricultural practices, distinctive pottery, and early developments in social structure and settlement patterns.

The Vinca culture is primarily associated with the central Balkans, specifically the region that spans parts of present-day Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, North Macedonia, and Croatia. The Vinca site near Belgrade (in modern-day Serbia) is considered one of the largest and most important settlements of this culture.

The Vinca people were among the first farmers in the region, transitioning from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more settled agricultural existence. They cultivated wheat, barley, and legumes, and raised animals such as cattle, sheep, and goats. Permanent settlements were established with houses made of wood and mudbrick. These settlements were often located near rivers or lakes, which provided fertile soil for agriculture and a source of water for domestic use.

The settlements of the Vinca culture were organized, with distinct residential and communal spaces. They often included silos for grain storage, suggesting that the people were able to store food surpluses.

The Vinca culture is renowned for its distinctive pottery, which was often decorated with geometric patterns, incised lines, and moulded shapes. Their pottery included both functional vessels (such as bowls, jugs, and storage jars) and ritualistic items. Ceramics were made from fine clay and were often painted with red, black, or white colours, and decorated with motifs such as spirals, zigzags, and meanders.

One of the more intriguing aspects of the Vinca culture is its potential link to an early form of writing, known as the Vinča symbols or Vinča script. These symbols are found on pottery, figurines, and other artifacts and are sometimes seen as a precursor to writing systems in Europe.

The symbols are abstract and still not fully understood, but some researchers believe they could represent an early form of proto-writing. The Vinča script has been a subject of debate, with some scholars arguing that these symbols are purely pictorial or symbolic, while others suggest that they may have been an early system of writing or record keeping.

The Vinca culture exhibited signs of social stratification, with evidence suggesting that there were both elite and common people within their settlements. This is seen in the larger, more elaborate houses found in certain areas, as well as the presence of specialized tools and ritualistic objects that may have been reserved for religious leaders or higher-status individuals. The culture engaged in extensive trade networks, as indicated by the presence of exotic materials such as obsidian, which was not locally available. This suggests the movement of goods over long distances across the Balkans and possibly beyond.

The Vinca people most likely practiced a form of animism, worshiping natural forces and ancestors. The presence of female figurines, fertility symbols, and ceremonial objects suggests a mother goddess cult, where fertility, creation, and the life cycle were central themes.

Animals also played an important role in their symbolism and may have had spiritual significance, as indicated by the zoomorphic figurines and motifs on pottery and artifacts.

The Vinca culture gradually declined around 4500 BCE, possibly due to changes in climate, shifts in trade routes, or the arrival of new cultures in the Balkans. Despite the decline of the Vinca culture, its legacy can be seen in later cultures of the region, particularly in the development of agricultural practices, pottery, and ritual practices. The Vinča symbols may also have influenced later writing systems in the region.

Vinca figurines

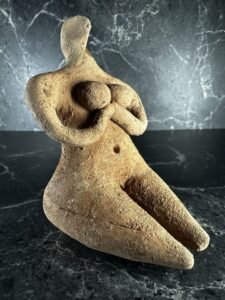

One of the most iconic elements of Vinca pottery is the small figurines of humanoid forms, often with exaggerated female features, such as large breasts and hips, which may indicate a focus on fertility and goddess worship.

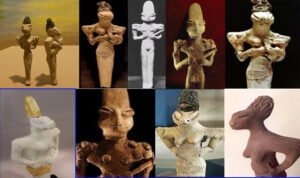

The Vinca figurines are some of the most significant artifacts from the culture. These small sculptures, often made of clay, depict humanoid figures, with an emphasis on female fertility symbols. Some of the figurines are abstract, while others have more detailed representations of the human body, but with exaggerated reproductive features. The figures are believed to have had ritualistic significance, possibly representing mother goddesses or fertility deities—a common feature in Neolithic societies. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines suggest a belief system that included deities or spirits associated with fertility, life cycles, and possibly ancestors.

Comparison with the Venus figurines

If we draw a comparison between the Vinca figurines and the Venus figurines from other Neolithic cultures, especially in their shared symbolic association with fertility, motherhood, and the feminine divine, then we can see some clear similarities. The Vinca figurines can be proposed as a regional interpretation of the Mother Goddess archetype, much like the well-known Venus figurines, and this can provide important insights into early human understandings of femininity, reproduction, and spiritual beliefs related to fertility.

The Vinca figurines are predominantly female, often featuring exaggerated reproductive features such as large breasts, wide hips, and full bellies. These figures are made from clay, and many of them are stylized, with abstract or simplified features, though some may exhibit a certain degree of detail, especially in the facial features and body shape.

Both the Venus figurines (from Palaeolithic cultures) and the Vinca figurines (from Neolithic cultures) share a focus on fertility and motherhood. The exaggerated female characteristics, such as large breasts and swollen bellies, strongly suggest that these figurines were intended to represent fertility goddesses, mother deities, or symbols of female reproductive power.

Much like the Venus figurines, the Vinca figurines are believed to have had ritualistic significance. They are thought to have been used in fertility rituals, prayers for successful childbirth, or as symbols of abundance and life-giving forces. They may have been placed in homes or temples to invoke the protection of these female deities or to secure successful pregnancies and nurturing of life. They are often small enough to fit in a pocket.

Both sets of figurines often emphasize traits associated with maternal femininity: large breasts, wide hips, and large bellies, suggesting an idealized or archetypal representation of femininity that focuses on reproductive health. The Venus of Willendorf, for example, and Vinca figurines, both exaggerate these features to represent the nurturing and generative power of the female form.

The earth goddess or Mother Earth concept is deeply embedded in these figurines, as fertility is often linked to the earth’s ability to nourish and sustain life. The wide hips of the figurines, for example, are often interpreted as symbols of the earth’s capacity to bear fruit, while swollen bellies emphasize pregnancy and the continuity of life, such goddesses are often linked with the birth of the Earth, and of the continued abundance of the Earth.

While Venus figurines emerged during the Palaeolithic era, when humans were primarily hunter-gatherers, the Vinca figurines appear in a Neolithic context, where societies had transitioned to agriculture and settled life. This shift in lifestyle likely affected the types of deities or symbols that people worshipped. The Neolithic world was increasingly centred around the idea of agriculture, planting, and sedentary living patterns. The divine masculine was also growing in importance.

The rise of agriculture and settlement in the Neolithic probably led to more complex ritual systems and a more formalized understanding of the female deity. The Vinca culture also reflects this development, as the figurines are found in settlements where people lived in permanent dwellings and engaged in agricultural practices.

These figures also reflect the demonstratable importance of the divine feminine during a time when women’s roles in agriculture and domestic life were central. The fertility goddess was probably not only associated with human reproduction but with the fertility of the earth as well, emphasizing the life-giving and nurturing qualities that women embodied in the early agricultural world.

In addition to their symbolism of fertility and motherhood, the Vinca figurines align closely with the larger tradition of mother goddesses found across ancient cultures. Many early agricultural societies revered a divine feminine associated with the earth, fertility, and motherhood. This was the case in Mesopotamian, Indus Valley, and Egyptian civilizations, where similar symbols of the female body represented the nurturing and creative power of the divine.

Small for portability?

The idea that the Vinca figurines may have been particularly associated with the ruling or priestly classes and may have been carried around as personal devotional objects fits well with the social dynamics and religious practices of early Neolithic societies.

As societies transitioned from nomadic to settled agricultural life, there was often a rise in social stratification—the creation of distinct social classes including priests, leaders, and elites. The Vinca culture experienced this shift, and evidence of social differentiation within their settlements supports the idea of a ruling or priestly class that may have been more mobile than the general populace.

The priestly or ruling classes were often responsible for religious rites, rituals, and making offerings to the gods. These individuals would have travelled between settlements or carried out ceremonial duties that involved personal consultations with the goddess or deities. As spiritual and temporal leaders, they would need to engage with the divine wherever they went, often in connection with rituals of fertility, harvests, or birth.

The small, portable size of the Vinca figurines would have made them ideal for this class of society, allowing them to carry the figurines without adding much weight or bulk. For individuals who were more mobile due to their spiritual duties, these figurines could have been personalized objects for consulting the goddess, invoking divine favour, or performing small rituals as they travelled.

In the context of increasing social complexity in Neolithic cultures, it’s plausible that the ruling and priestly classes not only used small figurines for personal consultations but also for asserting their divine right to rule. These figurines could have been viewed as embodiments of the goddess and a way to directly connect to the divine, reinforcing their authority and legitimacy in rituals or ceremonial settings.

As these classes were often the ones who held religious and political power, the Vinca figurines would have had both practical and symbolic importance. They allowed for a personal connection to the divine feminine—an essential part of both ritual practice and leadership. The portable nature of these figurines reflects the need for constant access to divine favour and support, reinforcing the elite’s role as intermediaries between the gods and their people, ensuring fertility, success, and prosperity.

The transition from portable, to temple objects

The transition from nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles to sedentary agricultural societies could have impacted the need for portable objects like the Vinca figurines. As early human societies became more settled, there was most likely a shift in how ritual objects were used, how religious practices were carried out, and whether these items continued to serve the same roles as they did during the earlier, more mobile periods.

Before the full settlement of the Vinca people, during the earliest phases of the Neolithic, human societies in the Balkans were still undergoing the shift from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to agriculture. In these early periods, people would have still maintained a level of mobility, even if they were gradually establishing permanent settlements. As hunter-gatherers transitioned into early agricultural societies, objects of personal spiritual significance, like these figurines, could have easily accompanied individuals as they moved between temporary or seasonal camps and early settlements.

As the Vinca culture became more sedentary, with the establishment of permanent villages and an emphasis on agriculture and animal husbandry, the need for personal portability of religious objects would likely have declined. People would have spent more time in a fixed location, where the need to carry figurines or ritual items around would have diminished, as the central places of worship and ritual could be more established.

In these sedentary societies, it is likely that rituals and religious practices became more community-focused. Temples or sacred spaces would have been set up in settlements, and larger, communal figurines or altars may well have taken the place of personal portable objects. The rise of organized ritual in permanent settlements would have meant that instead of individuals needing to carry their personal religious objects around, there would have been dedicated spaces for spiritual practice.

While it is clear that the Vinca figurines became important in their early agricultural society, archaeological evidence suggests that over time, other forms of religious artifacts began to be used, which could have included larger statues, ritual tools, or even the construction of more permanent sacred spaces like temples.

There are a number of examples and broader trends in archaeology that support the idea that the small, portable figurines of the Vinca culture likely evolved as society transitioned from nomadic or semi-nomadic to more sedentary agricultural communities. These examples not only support the evolution of religious practices in response to changes in social organization, but also show how portable figurines gave way to larger, more communal objects as settlements grew and religious systems became more structured.

Venus Figurines (Palaeolithic – c. 40,000 to 15,000 BCE): The Venus figurines, such as the Venus of Willendorf, are famous for their small size and exaggerated female forms, which served as symbols of fertility, life-giving forces, and motherhood. These figurines were likely carried by individuals and used in personal rituals. The small size of these figures reflects the mobile lifestyle of Palaeolithic humans, who were still in the hunter-gatherer phase.

Vinca Figurines (Neolithic – c. 5700 to 4500 BCE): The Vinca figurines, while still emphasizing fertility and female symbolism, also represent the transition to sedentary life. While many of the earliest Vinca figurines were still small and portable, their use likely mirrored that of the Venus figurines—primarily for personal religious practices. However, as the Vinca culture progressed toward a more agricultural and settled society, larger figurines and ritual objects became increasingly common, reflecting the shift toward more organized religious practices in community spaces.

The Vinca culture later shows evidence of larger, communal religious items, such as temple structures, ritual artifacts, and larger figurines. These developments suggest that, as Vinca settlements became more permanent and complex, the religious practices likely moved from individual, mobile rituals to more organized, communal religious practices.

Mesopotamia: Early Mesopotamian societies (c. 5000 BCE) were also transitioning from nomadic to sedentary agricultural lifestyles. In this context, the small figurines used for personal rituals in earlier periods were replaced with larger statues and temple altars in more settled urban societies. For example, statues of gods like Ishtar and Nanna became central to religious practice in temples, reflecting the growing importance of communal worship over individual ritual practices.

Indus Valley Civilization: Similarly, the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300 to 1300 BCE) used small seals and figurines, which were likely used for personal rituals or to represent goddess figures. However, as cities became more organized, large public baths and ritual spaces in places like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa reflected a shift to communal and state-sponsored religious practices, suggesting that smaller objects of personal significance began to be replaced by larger, communal representations.

By the time of Bronze Age cultures like the Mycenaeans (c. 1600–1100 BCE), religious practices had become largely communal, with large temples and public altars becoming the centre of worship. The shift to more centralized and state-controlled religious systems shows how portable religious objects began to lose their centrality as worship became more organized and public. Smaller idols and figurines may have continued to exist, but they were now likely viewed as personal tokens rather than central to large-scale religious rituals.

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!