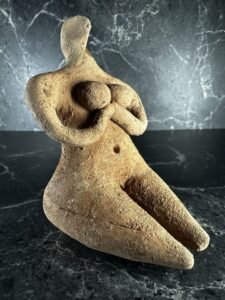

Ninhursag, also known as Ninmah, Damgalnuna, Nintu, Belet-Ili, Shassuru, and Damkina or Ninursag, was an ancient Sumerian mother goddess associated with fertility, mountains, and the creation of life. She was one of the seven great deities of Sumer and was often depicted as a nurturing figure, symbolizing the earth and its ability to produce life. Ninhursag was believed to have created both divine and mortal beings, earning her the titles “Mother of the Gods” and “Mother of Men”. Her myths often involve her interactions with other gods, such as Enki, and she played a significant role in Sumerian religious beliefs and practices.

Ninhursag appears in several notable Sumerian myths. One of the most famous is the story of Enki and Ninhursag, where Enki, the god of wisdom and water, falls ill due to a curse from Ninhursag. She eventually heals him by giving birth to healing deities. Another significant myth is **Enki and Ninmah**, a creation story where Ninhursag (as Ninmah) and Enki compete to create humans. Additionally, she is featured in the **Anzu Epic** as the mother of Ninurta. These stories highlight her roles in creation, healing, and her interactions with other deities.

The Anzu Epic

The Anzu Epic is a fascinating tale from Mesopotamian mythology, featuring the creature Anzu, also known as Zu or Imdugud. Anzu is depicted as a massive bird with the head of a lion, capable of breathing fire and water. The epic primarily revolves around Anzu stealing the Tablet of Destinies from the god Enlil, which grants control over the universe. This theft causes chaos, and the hero god Ninurta (or Ningirsu in earlier versions) is tasked with retrieving the tablet. The story highlights themes of power, divine authority, and the struggle to restore order. Anzu’s mythological significance extends beyond this epic, symbolizing the fusion of military might and scholarly wisdom in ancient Mesopotamian culture.

In this myth, Ninhursag plays a supportive and nurturing role. She is the mother of Ninurta, the hero god tasked with retrieving the stolen Tablet of Destinies from Anzu. Ninhursag speaks in favour of her son’s actions, demonstrating her protective nature. Her support is crucial in motivating Ninurta to confront Anzu and restore order. This highlights her importance as a maternal figure and a deity who influences the destinies of gods and humans alike.

The myth of Enki and Ninhursag

The myth of Enki and Ninhursag is a fascinating tale from Sumerian mythology. It begins in the paradise-like land of Dilmun, where Ninhursag, the mother goddess, resides.

Dilmun, often described as a paradise-like land, holds a significant place in ancient mythology and history. Located in the Persian Gulf, encompassing modern-day Bahrain, Kuwait, and parts of Saudi Arabia, Dilmun was a major trading hub between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilization. In Sumerian mythology, Dilmun is depicted as a utopian garden where sickness and death were absent, and it is mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh as a place of purity and abundance. This idyllic portrayal has led some scholars to suggest that Dilmun may have inspired the biblical Garden of Eden story. The civilization thrived from the late 4th millennium BC until around 538 BC, playing a crucial role in the region’s trade and cultural exchanges.

In the myth, Enki, the god of wisdom and water, falls in love with her, and they have a daughter named Ninsar, the goddess of plants. Enki’s desire leads him to have children with his own descendants, resulting in a series of divine births.

Eventually, Enki falls ill due to consuming forbidden plants. Ninhursag, angered by his actions, curses him, causing his body to suffer. However, she later takes pity on him and heals him by creating eight healing deities from his ailing body parts. This myth highlights themes of creation, the interconnectedness of life, and the consequences of desire and transgression.

The eight healing deities created by Ninhursag each had specific roles and abilities:

Abu – the god of plants, associated with the healing properties of vegetation.

Nintulla (or Nintul) – linked to the region of Makan, possibly overseeing its health and prosperity.

Ninsutu – a goddess of healing, focusing on medical and therapeutic practices.

Ninkas – the goddess of beer, believed to have healing and purifying properties.

Nanshe – the goddess of magic and wisdom, using her knowledge for healing.

Azimua – another goddess of healing, likely involved in curing diseases.

Ninti – a goddess of healing, whose name means “Lady of the Rib,” symbolizing life and health.

Enshag (or Enshagag) – a deity associated with healing, possibly through divine intervention.

The healing deities created by Ninhursag were invoked in prayers and rituals to address various health issues. For example, Ninkasi, the goddess of beer, was believed to have purifying and healing properties, so people might pray to her for ailments related to digestion or purification. Similarly, Ninti, whose name means “Lady of the Rib,” was associated with life and health, and people might seek her aid for general healing. These prayers were part of a broader practice that combined religious belief, magic, and medicinal substances to treat illnesses.

The myth of Enki and Ninmah

The myth of Enki and Ninmah is a fascinating Sumerian creation story. In this tale, the gods are burdened with the toil of maintaining the earth and complain to Namma, the primeval mother. She urges her son Enki, the god of wisdom, to create a substitute to relieve the gods of their labor.

In Mesopotamian mythology, the lesser gods, known as the Igigi, were burdened with laborious tasks such as digging canals and maintaining the irrigation systems essential for agriculture. These tasks were physically demanding and relentless, leading to their eventual rebellion. To alleviate their suffering, the higher gods decided to create humans to take over these duties. This creation myth underscores the importance of agriculture and irrigation in ancient Mesopotamian society and highlights the divine origins attributed to human labor.

In Sumerian mythology, the gods created humans primarily to relieve themselves of the burdensome tasks associated with food production and other labor. This implies that the gods needed sustenance, but the myths do not always provide detailed explanations about why divine beings would require food. However, some texts suggest that the gods consumed special foods and drinks that granted them strength and immortality. For instance, Ninhursag’s milk, associated with the goddess of fertility, was believed to make gods and kings strong and immortal. This need for sustenance might symbolize the gods’ connection to the natural world and their dependence on the offerings and rituals performed by humans.

Enki and Ninmah then engage in a competition to create humans from clay. This myth highlights themes of creation and the inherent imperfections of humanity, as the beings they create are flawed. The story underscores the idea that human imperfections are a natural part of existence, shaped by divine hands.

In the myth of Enki and Ninmah, the competition between the two deities is both creative and humorous. After the gods complain about their labor, Enki and Ninmah decide to create humans to take over these tasks. They begin by fashioning humans from clay, but their creations are imperfect. Ninmah creates six different humans, each with a unique flaw: one cannot bend his hands, another has vision problems, and others have various disabilities. Enki then tries to improve upon her creations but also ends up with flawed beings. This competition highlights the theme of human imperfection and the playful, yet serious, nature of the gods’ creative endeavours.

In the myth of Enki and Ninmah, Ninmah creates six humans, each with a distinct flaw. The first human cannot bend his outstretched hands. The second has impaired vision. The third has paralysed feet. The fourth suffers from constant pain. The fifth is unable to control his urine. The sixth is a woman who cannot give birth. These imperfections highlight the theme of human frailty and the inherent flaws in creation.

Enki responded to Ninmah’s flawed creations with a mix of humour and wisdom. He acknowledged the imperfections of the beings she created and decided to counterbalance their fates. For each flawed human, Enki found a way to integrate them into society. For example, he assigned the man who couldn’t bend his hands to serve the king, and the one with impaired vision to be a musician. This response highlights Enki’s resourcefulness and the idea that every individual, despite their flaws, has a place and purpose.

Enki decreed that the woman who was unable to give birth would belong to the queen’s household. In some versions of the myth, she was specifically assigned the role of a weaver. This decision reflects Enki’s wisdom in finding a place and purpose for each individual, regardless of their imperfections.

Assigning the woman who couldn’t give birth to the queen’s household held significant meaning. It ensured that she had a respected and secure place in society, despite her inability to fulfil the traditional role of motherhood. By integrating her into the queen’s household, Enki demonstrated that every individual, regardless of their imperfections, has value and a purpose. This act also highlighted the importance of compassion and inclusivity in the divine order.

Other myths exploring creation and imperfection

Several other Sumerian myths explore themes of imperfection and creation. One notable example is the Eridu Genesis, which describes the creation of humanity by the gods and the subsequent flood sent to destroy them due to their imperfections and noise.

The Debate between Sheep and Grain is a fascinating Sumerian myth dating back to around 2000 BCE. This myth is part of a genre known as disputations, where personified elements of nature argue over their importance. In this particular debate, Grain and Sheep each present their case to the gods, arguing over which is more essential for sustaining humanity. Grain argues that it is the foundation of human sustenance, providing food and drink, while Sheep counters that it offers clothing and other necessities.

Ultimately, Grain is declared the winner, as it is deemed more crucial for human survival. This myth not only highlights the agricultural practices of ancient Sumer but also reflects the societal tensions between farmers and herders, who both relied on the land for their livelihoods. The debate was likely performed as a form of entertainment and education, illustrating the interdependence of different aspects of society and the natural world.

The Debate between Winter and Summer is an exploration of the dynamic interplay between these two contrasting seasons. Winter, with its cold, quiet, and often harsh conditions, represents a time of rest and reflection in nature. In contrast, Summer, with its warmth, vibrancy, and abundance, symbolizes growth, activity, and life. This rivalry highlights the balance in nature, where each season has its own role and importance, contributing to the cycle of life.

The imperfections in each season also reflect the imperfections in nature itself. Winter’s harshness can be seen as a necessary challenge that prepares the world for the renewal and growth of Summer. Similarly, Summer’s intense heat and storms can be viewed as forces that shape and nurture the environment. This debate underscores the idea that both seasons, despite their flaws, are essential to the natural order, creating a harmonious balance that sustains life on Earth.

Symbology

Ninhursag, the ancient Sumerian mother goddess, is associated with several symbols that reflect her divine powers and connections to nature and fertility. Some of these symbols include:

The serpent: Symbolizing wisdom, transformation, and the cycle of life.

The mountain: Representing stability, strength, and the earth as a nurturing force.

The omega symbol: Often interpreted as a schematic representation of a woman’s hair or a stylized womb.

These symbols emphasize her role as a protector of life, a source of sustenance, and a nurturing figure in Sumerian mythology.

The omega symbol (Ω) has a rich history and diverse applications. In ancient Mesopotamian mythology, Ninhursag is often depicted with a symbol resembling the Greek omega. This symbol, thought to represent the uterus and the blade used to cut the umbilical cord, underscores her role as a nurturing mother and creator.

The symbols of Alpha and Omega are used in various beliefs and contexts beyond Christianity. In ancient Greek religion, these letters symbolized the beginning and end of the Greek alphabet, representing the completion and entirety of knowledge. In Judaism, a similar concept exists with the word “emet” (truth), composed of the first and last letters of the Hebrew alphabet, symbolizing God’s truth and completeness. Additionally, in ancient cultures like Egypt and Rome, the symbols represented divine power or energy responsible for all creation.

In the context of ancient Mesopotamian mythology, the “alpha” figure could be considered Anu, the sky god, who was often regarded as the supreme deity and the father of the gods. Anu’s position as the highest god aligns with the concept of “alpha,” symbolizing the beginning and the ultimate authority in the pantheon.

She is commonly depicted seated upon or near mountains, sometimes with her hair in an omega shape, and wearing a horned head-dress and tiered skirt. The colours and aesthetic elements linked to her typically include earthy tones, reflecting her connection to the mountains and the earth.

Rituals in Sumer

There were specific rituals and ceremonies in ancient Mesopotamia to invoke healing deities. These rituals often involved incantations, offerings, and symbolic actions. For example, the Marduk-Ea incantation was a well-known healing spell used in exorcistic rituals to cure illnesses believed to be caused by demonic possession. Priests would recite these incantations, sometimes performing ritual dramas where they played the roles of gods.

Another example is the worship of Gula, the goddess of healing, who was often invoked in rituals involving dogs, as they were believed to have healing properties. Offerings of food, drink, and other items were made to the deities, and prayers were recited to seek their intervention in healing. These ceremonies were integral to the spiritual and medical practices of the time, blending religious belief with early forms of medicine.

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!