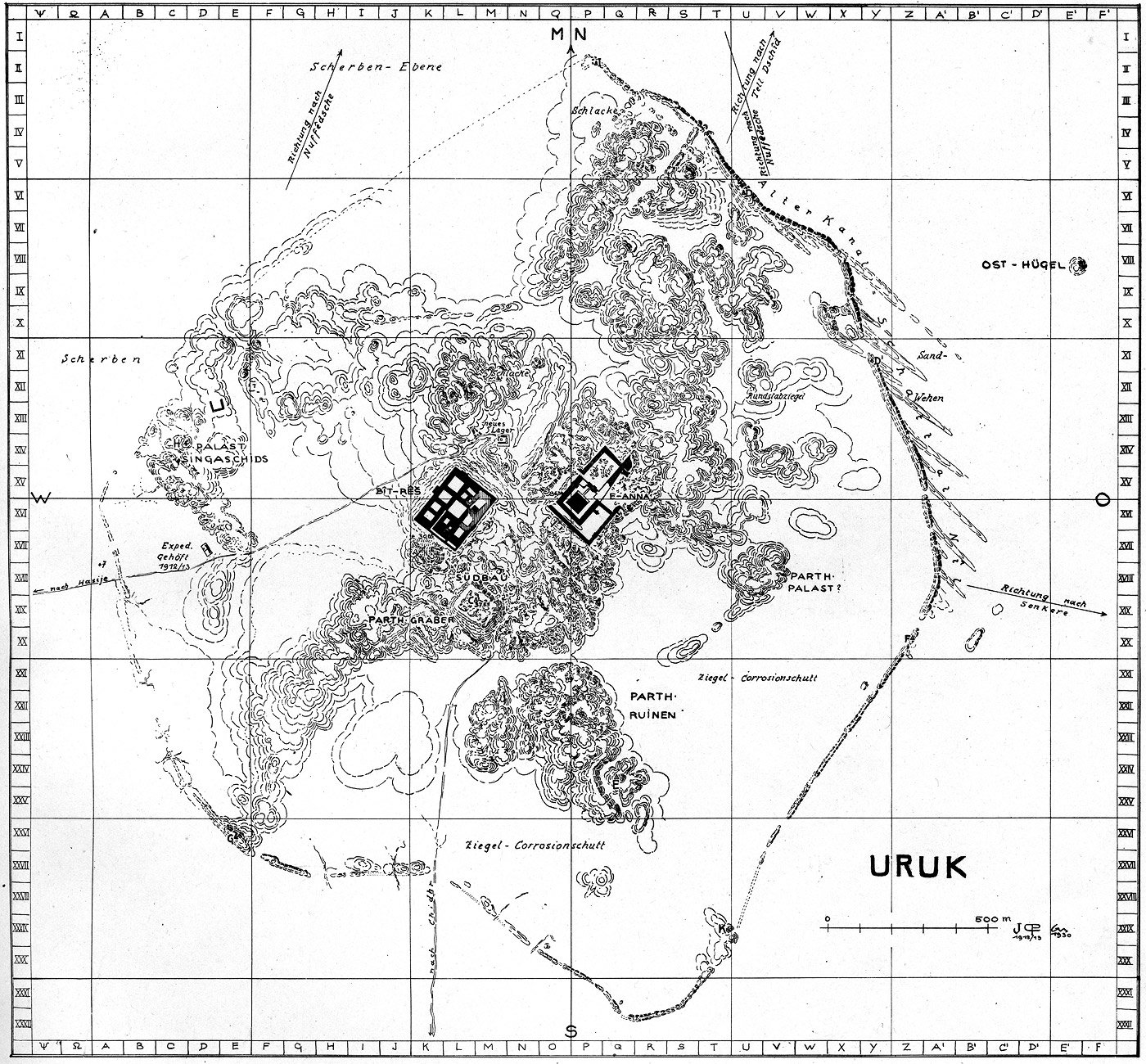

The City of Uruk

Uruk, known today as Warka, was one of the most significant early cities in ancient Mesopotamia, located in the southern region of Sumer. Founded around 4500 BCE, Uruk is often credited as the birthplace of writing, around 3200 BCE, marking a pivotal moment in human history.

This city was a hub of cultural and architectural innovation, including the development of monumental architecture and the ziggurat, a massive structure that would influence Mesopotamian temple design for millennia. The city’s influence peaked during the Uruk period (4000-3100 BCE), a time when urbanization rapidly advanced across Mesopotamia.

Uruk was not only a political and economic centre but also a religious one, with the famous King Gilgamesh, whose epic tale has survived through the ages, purportedly ruling there in the 27th century BCE. The city’s decline began around 3000 BCE, but it remained inhabited until approximately 300 CE. Its abandonment was likely due to a combination of depleted resources and changing political landscapes.

Excavations at Uruk began in the mid-19th century, revealing a wealth of artifacts and cuneiform tablets that have provided invaluable insights into early urban life and the complexities of Sumerian society.

The ziggurat in Uruk, a true marvel of Sumerian architecture, stands as a testament to the ingenuity and spiritual devotion of ancient Mesopotamian civilization. This massive structure, known as the White Temple, was dedicated to the sky god Anu and dates back to the late Uruk period, around 3517-3358 BCE. Constructed atop a raised platform, the ziggurat’s design featured four sloping sides, resembling a truncated pyramid, and was made primarily from mud-bricks, the material of choice in the Near East due to the scarcity of stone.

The White Temple

The White Temple, which crowned the ziggurat, was a gleaming beacon of worship, coated in whitewash that shone brilliantly under the sun. The temple’s elevated position was not only a symbol of divine ascension but also a reflection of the god’s political authority over the city. The ziggurat itself was intricately designed with recessed bands that created a striking pattern of light and shadow, enhancing its visual impact and asserting its presence as the city’s spiritual and political core.

Access to the temple was a journey of reverence, beginning with a steep stairway leading to a ramp that wrapped around the ziggurat, guiding worshippers and priests to the sacred space where the divine was believed to dwell. The construction of such a monumental edifice would have required a colossal effort, with estimates suggesting that 1500 labourers might have worked for approximately five years to complete the final major revetment of its terrace. This undertaking reflects the importance of the ziggurat within Uruk’s society, where religious belief and state authority were deeply intertwined.

The ziggurat’s foundation was designed to be both firm and waterproof, employing bitumen to coat the top of the platform, ensuring the temple’s endurance against the elements. The White Temple’s interior, like its exterior, was completely whitewashed, creating an environment of purity and brilliance that mirrored the celestial domain of Anu.

The legacy of the White Temple and its ziggurat extends beyond its physical remnants; it represents the culmination of cultural and religious practices that defined early urban societies. Its construction not only exemplified the architectural capabilities of the time, but also the social and religious structures that governed the lives of the Uruk inhabitants. The ziggurat of Uruk, therefore, is not merely an ancient structure but a symbol of the profound human desire to connect with the divine and the cosmos.

Evidence of Ritual at the White temple

The specific rituals conducted within the White Temple of Uruk, dedicated to the sky god Anu, remain largely a mystery due to the scarcity of detailed records from that period. However, it is widely believed that the activities were of significant religious and political importance, reflecting the theocratic nature of Sumerian society. The temple’s design suggests that it was a site for high ceremonies, likely involving only the elite, such as priests and royalty.

The elevated position of the temple atop the ziggurat symbolized a bridge between the earthly and the divine, and the rituals performed there would have been aimed at maintaining the favour of the gods, which was essential for the city’s prosperity and power. Offerings, prayers, and sacrifices were common elements of Mesopotamian religious practices, and it is probable that such activities took place within the White Temple.

The layout of the temple, with its single, narrow doorway, indicates that the space was highly restricted, which would have added to the exclusivity and sanctity of the rituals. The whitewashed walls of the temple, gleaming in the sunlight, would have created an atmosphere of purity and transcendence, further enhancing the spiritual experience of the ceremonies.

Given the temple’s dedication to Anu, the rituals likely had an astral aspect, with observations of the sky and celestial bodies playing a role in the timing and nature of the ceremonies. The priests, seen as intermediaries between the divine and the mortal realms, would have performed intricate rites to ensure cosmic harmony and to seek divine wisdom and guidance for the ruler of Uruk.

The ziggurat itself, with its imposing presence, served as a constant reminder of the god’s omnipresence and theocratic rule. The processional route to the temple, involving a steep stairway and a ramp, was part of the ritualistic journey, preparing the participants for their encounter with the divine. The physical exertion required to ascend to the temple mirrored the spiritual effort believed necessary to commune with the gods.

Artefacts found during the excavation of the White Temple

The White Temple of Uruk, despite its monumental architectural significance, yielded relatively few artifacts during excavations. However, the objects that were discovered provide a fascinating glimpse into the activities that took place within this ancient religious edifice. Archaeologists found approximately 19 tablets made of gypsum on the temple’s floor. These tablets were not ordinary; they bore the impressions of cylinder seals, which were used as administrative tools to record and authenticate goods and transactions. The presence of these tablets suggests that the White Temple also served an administrative function, possibly related to the management of resources or the recording of offerings to the deity Anu.

The cylinder seal impressions on the tablets are particularly noteworthy because they reflect the complexity of Uruk’s economic and religious systems. Cylinder seals were intricately carved with images and symbols that represented individuals, organizations, or events, and were rolled onto the wet clay to leave an impression. The fact that these seals were found in the White Temple indicates that the temple was a centre for both worship and bureaucratic activity. This dual role of the temple underscores the intertwined nature of the sacred and the secular in Sumerian society, where religious institutions often managed economic affairs and provided social services.

The scarcity of artifacts in the White Temple could be attributed to several factors. Many valuable items may have been removed or plundered in antiquity, or that the temple was cleared of objects during its active use to maintain a sacred and uncluttered space for worship. Additionally, the materials used for other artifacts may have deteriorated over time, leaving behind only those made of more durable substances like gypsum.

The artifacts found in the White Temple, while few, are invaluable to our understanding of Uruk’s society. They offer insights into the administrative and religious practices of one of the world’s earliest urban civilizations, and highlight the sophistication of the Sumerians in both governance and spiritual matters. The tablets, with their seal impressions, stand as silent witnesses to the bustling activity that once filled the White Temple, where the divine and the mundane coexisted within its whitewashed walls.

The temple’s most striking feature was its whitewashed walls, which would have gleamed brilliantly in the sunlight, serving as a beacon of reverence and awe. This bright white finish gave the temple its name and added to the visual impact of the structure, emphasizing its sacred nature.

Clay Cone Mosaics

In addition to the whitewash, the temple featured a unique form of decoration known as clay cone mosaics. This involved embedding clay cones with coloured tops into the mud plaster of the walls, creating a patterned, textured surface. The cones could be arranged in various designs, and the tops painted in different colours, possibly to create geometric patterns or symbolic imagery. This technique was a characteristic form of decoration in Uruk and provided a durable and visually striking embellishment that could withstand the harsh climate of the region.

The ziggurat itself, upon which the White Temple sat, also contributed to the site’s decorative scheme. Its broad, sloping sides were broken up by recessed stripes or bands, which created a stunning pattern of light and shadow in the morning or afternoon sunlight. This design feature would have made the ziggurat and the temple it supported a visual focal point of the city, reflecting the theocratic political system where the temple was a symbol of the god’s political authority.

While no extensive frescoes or intricate murals have been uncovered, the simplicity and elegance of the White Temple’s decorations are a testament to the Sumerian aesthetic, which favoured clean lines, geometric forms, and a harmonious blend of architecture and artistry. The decorations of the White Temple were not merely ornamental; they were deeply symbolic, reflecting the religious beliefs and the cultural values of the people of Uruk.

The archaeological evidence suggests that the Sumerians placed a high value on the interplay of form and function, and the White Temple’s decorations were an integral part of its spiritual and communal role. The temple’s appearance would have conveyed messages about the divine, the cosmos, and the social order to all who beheld it, reinforcing the temple’s central place in the life of the city.

The clay cone mosaics that adorned the White Temple of Uruk were a distinctive feature of Sumerian decorative arts. These cones were typically made from baked clay or stone and were embedded into the walls with their coloured ends exposed, creating intricate patterns. The colours used were primarily red, black, and white, which were not only visually striking against the mud plaster walls but also held symbolic significance. Red might have symbolized life or blood, black could represent the fertile earth or the netherworld, and white may have denoted purity or the divine essence.

These colours were chosen for their contrast and visibility, ensuring that the patterns they formed were clearly discernible from a distance. The use of such a limited palette also reflects the natural resources available to the Sumerians and their mastery in creating a vibrant visual language with minimal elements. The application of colour in the mosaics would have been a laborious process, with each cone being painted by hand before being set into the plaster. This meticulous craftsmanship highlights the importance of the temple as a centre of religious and communal life.

The patterns created by the clay cones were likely geometric, possibly reflecting the weaving of reed mats, a common household item in Sumerian homes. This connection between everyday objects and monumental architecture suggests a cultural continuity and a shared aesthetic value system. The geometric patterns could also have had symbolic meanings, representing the order of the cosmos or the structured society of Uruk.

The choice of colours and the patterns they formed would have been deeply symbolic, with each hue and shape carrying multiple layers of meaning. In the context of the temple, these decorations would have communicated ideas about the divine, the natural world, and the social hierarchy. The visual impact of the mosaics would have reinforced the temple’s sacred atmosphere, creating a space that was both awe-inspiring and reflective of the Sumerians’ complex belief system.

The origin of the name Uruk

The origin of the name “Uruk” is rooted in ancient Mesopotamian history and language. It is believed to have derived from the Sumerian word “Unug,” which was the city’s original name. The word “Unug” () is derived from the Sumerian term for “abode” or “site,” often referring to a deity’s earthly dwelling. This term evolved to denote the city of Uruk, reflecting its significance as a major urban centre and religious site

The Akkadian form of the name, “Uruk,” became the standard term used in later texts. The name “Uruk” () is believed to be a phonetic alteration of “Unug,” influenced by the Akkadian word “uru,” meaning “city” or “place of dwelling”. This transition in nomenclature reflects the linguistic evolution and cultural exchanges that occurred in the region over time. The Sumerian language, which is considered a language isolate, has contributed significantly to the lexicon of later Mesopotamian languages, including Akkadian, which was a Semitic language.

The name “Uruk” itself is indicative of the city’s prominence and influence in ancient times. As one of the earliest and most important cities in Mesopotamia, Uruk played a pivotal role in the development of urban civilization and culture. The city is often credited as the birthplace of writing, with the earliest form of cuneiform script emerging there. This innovation in writing technology had profound implications for the administration, literature, and history of the ancient world.

Furthermore, the name “Uruk” has been linked to the Arabic word for Iraq, suggesting a deep historical connection between the ancient city and the modern nation-state. While some scholars propose that the name of the country of Iraq is directly derived from “Uruk,” others suggest that it is more likely borrowed via Middle Persian and Aramaic routes, which may still ultimately refer to the Uruk region of southern Mesopotamia. This etymological journey from “Unug” to “Uruk” to “Iraq” illustrates the enduring legacy of the ancient city and its lasting impact on the region’s identity.

The significance of Uruk extends beyond its name; the city’s history is marked by remarkable achievements in architecture, such as the development of the ziggurat, and in governance, with the city-state model that influenced the political landscape of ancient Mesopotamia. The legendary King Gilgamesh, known for the epic tale that bears his name, is said to have ruled Uruk, further cementing the city’s place in literary and historical tradition.

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!