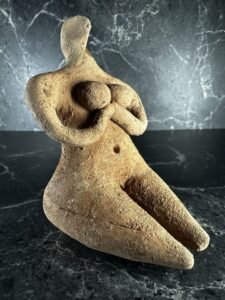

Venus of Willendorf, Willendorf Museum

When did the suppression of the divine feminine begin?

The suppression and defacing of the divine feminine appears to have begun as part of cultural and religious shifts associated with societal transitions from egalitarian or matrilineal societies to more hierarchical and patriarchal ones. While pinpointing an exact time is challenging due to the gradual and varied nature of these changes across regions, archaeological and anthropological evidence suggests some key periods and potential clashes that contributed to this phenomenon.

Neolithic to Bronze Age Transitions (c. 5000–3000 BCE)

The Divine Feminine in Prehistory: Archaeological evidence from the Neolithic period (c. 10,000–4000 BCE) shows widespread veneration of feminine symbols associated with fertility, life, and nature.

Examples include the Venus figurines (e.g., Venus of Willendorf) and the many representations of earth goddesses in Europe, the Near East, and Asia.

These societies often had egalitarian structures or matrilineal traditions, with women holding significant roles in spirituality and governance.

The Kurgan Hypothesis: Around 3000 BCE, the Kurgan culture (Indo-European pastoralists) began expanding from the steppes of Central Asia into Europe, the Near East, and India.

The Kurgan people were likely male-dominated, warrior-focused, and hierarchical, clashing with more agrarian, goddess-centred societies such as those in Old Europe (e.g., the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture).

The resulting cultural integration or conquest led to a decline in goddess worship and the rise of male-dominated pantheons, as seen in Indo-European mythologies (e.g., Zeus replacing Gaia in Greek mythology).

Mesopotamia and the Early States (c. 3000–2000 BCE)

Shift from Goddesses to Gods: In early Sumerian religion, goddesses like Inanna/Ishtar were central figures representing love, fertility, and war. However, as city-states grew more hierarchical, male gods like Marduk in Babylon gained prominence, often absorbing the roles and attributes of earlier goddesses.

The Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic, recounts how the male god Marduk defeated the primordial goddess Tiamat, symbolizing the subjugation of feminine chaos by masculine order.

Patriarchal Influence: Male kings claimed divine legitimacy by associating themselves with male gods, further marginalizing feminine spiritual authority.

Egypt: The Rise of Male-Centred Power (c. 1500 BCE)

Early Feminine Power: Early Egyptian religion prominently featured goddesses like Isis, Hathor, and Sekhmet, often as co-equals or complements to male gods.

Female rulers like Sobekneferu and Hatshepsut wielded power and maintained strong religious ties to the divine feminine.

Shift in the New Kingdom: By the New Kingdom (c. 1500–1070 BCE), there was a greater emphasis on male gods (e.g., Amun-Ra) and pharaohs as their embodiments. The systematic erasure of Hatshepsut’s legacy reflects the discomfort with women in positions of power.

While goddesses remained important, their roles were increasingly framed as supportive or subordinate to male deities.

Greek and Roman Transitions (c. 1000 BCE–500 CE)

Greek Patriarchy: Early Greek myths featured powerful goddesses like Gaia and Rhea, but later myths saw them overshadowed by gods like Zeus and Apollo.

The patriarchal reorganization of the pantheon reflected societal shifts toward male-dominated governance and military culture.

Roman Adaptations: Roman religion absorbed Greek deities but further subordinated feminine aspects, often associating them with specific, limited roles (e.g., Venus for love, Ceres for agriculture).

The Roman Empire’s expansion often suppressed local goddess traditions, replacing them with the state-sanctioned male pantheon.

The Rise of Monotheism (c. 500 BCE–500 CE)

Zoroastrianism: Zoroastrianism, one of the earliest monotheistic religions, centred around Ahura Mazda, a male deity. While feminine figures like Anahita retained some prominence, they were often reinterpreted or side-lined.

Judaism and Christianity: Early Judaism moved away from polytheistic traditions that included goddesses like Asherah, who was once venerated alongside Yahweh. Asherah’s worship was systematically suppressed, and she was labelled a forbidden idol.

Christianity, emerging from Judaism, reinforced patriarchal structures by emphasizing a male God and excluding feminine figures from positions of divine authority (e.g., side-lining Mary Magdalene).

Feminine Suppression as a Cultural Clash

The recurring pattern suggests that the suppression of the divine feminine often arose from cultural clashes between matrifocal or goddess-centred societies and patriarchal, conquest-driven societies. Examples include:

- The Indo-European expansion into Old Europe.

- The spread of monotheism displacing polytheistic traditions.

- The Christianization of indigenous cultures during European colonization.

Image: Venus of Willendorf, Willendorf Museum.

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!