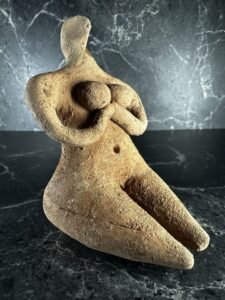

Mother Goddess from Çatalhöyük

The Waxing and Waning of the Divine Feminine Through Time

Introduction to the Divine Feminine

The concept of the divine feminine has its roots in the worship of goddesses associated with fertility, life-giving forces, and the earth’s abundance. This archetype was central to religious practices, particularly in the Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods, and the Mother Goddess was seen as a manifestation of the earth’s fertility, the cycles of nature, and human reproduction. These goddesses symbolized the nurturing and creative powers of femininity and were honoured through symbolic objects like figurines, artwork, and ritual sites.

The Divine Feminine in the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Periods

Venus Figurines (c. 30,000–10,000 BCE)

The Venus figurines are perhaps the most famous representations of the Mother Goddess archetype. These small, portable statues typically feature exaggerated female traits such as large breasts, wide hips, and prominent buttocks—features associated with fertility, reproduction, and life-giving forces. The Venus figurines were not confined to a specific region but were found across much of Europe, indicating a widespread belief in a fertility goddess or the divine feminine during the Paleolithic and early Mesolithic periods.

Key examples of these figurines include:

- Venus of Willendorf (c. 28,000–25,000 BCE), found in Austria.

- Venus of Laussel (c. 25,000 BCE), discovered in France.

- Venus of Hohle Fels (c. 35,000 BCE), found in Germany.

These figurines were not merely decorative but were likely used in ritualistic contexts, invoking divine fertility and protection. Scholars have suggested that these figures may have been used in shamanistic rituals, spiritual ceremonies, or as fertility charms.

Vinca culture Mother Goddess figurine.

Neolithic Figurines (c. 10,000–3,000 BCE)

Moving into the Neolithic period, we see a continuation of the Mother Goddess theme, although with slight variations. In this period, societies began to shift from nomadic to sedentary agricultural life, and the fertility goddess evolved to reflect the changing relationship between humans and the land.

Neolithic figurines from cultures such as the Vinca (c. 5700–4500 BCE), Starčevo (c. 6200–5000 BCE), and Çatalhöyük (c. 7400–6000 BCE) show similarly exaggerated female forms, emphasizing fertility and earthly abundance. These societies were deeply reliant on the fertility of the land for agriculture, and the goddess came to represent the earth’s ability to sustain life.

The Vinca culture in south-eastern Europe produced small clay figurines with exaggerated female features, which may have been used in rituals related to fertility and agricultural prosperity.

The Starčevo culture in the Balkans also produced figurines, many of which feature pronounced female forms with large hips, linking them to the themes of fertility and reproduction.

Other Cultures with Goddess Figurines

Malta: The Ggantija temples on the island of Gozo, dating from c. 3600–2500 BCE, are famous for their association with goddess worship. The Ggantija temples are among the oldest megalithic structures in the world and are believed to have been dedicated to a Mother Goddess, with numerous female figurines found in the area. These figurines, often stylized with large, rounded bodies, again symbolize the fertility of the land and the central role of the divine feminine in sustaining life.

Near East: In the Near East, early evidence of goddess worship can be found in the figurines of cultures such as the Sumerians, Hittites, and Akkadians. These cultures often worshipped powerful female deities associated with fertility, creation, and the earth. The Mother Goddess figure in these cultures is frequently linked to the cycles of nature and the fertility of the land. For example, the Mother Goddess figurines from Mesopotamia (dating to around 3000 BCE) show similar themes of life-giving forces and fertility, often linked to agricultural rituals.

Widespread Nature of the Goddess Archetype

The Mother Goddess figure is not limited to one particular region but . These figurines from Venus figures to goddesses appear in early agricultural societies across Europe, the Near East, and parts of Africa. They all share similar themes of fertility, nature, and the divine feminine as a powerful, life-giving force. These figurines were widespread, suggesting that the Mother Goddess archetype was a universal symbol in early human spirituality.

The iconography of the Mother Goddess in these societies serves as a reflection of the central role of the divine feminine in their understanding of the world. From the Venus figurines of Palaeolithic Europe to the fertility goddess representations in Neolithic Malta and the Near East, these figurines highlight the belief that life, fertility, and the earth’s cycles were sacred and deeply connected to the feminine principle.

Decline of the Divine Feminine

As agriculture became more complex and societies shifted to more patriarchal structures, the prominence of the Mother Goddess waned. With the rise of male gods in the early Bronze and Iron Ages, and the development of monotheistic religions in the following centuries, the divine feminine began to lose its central place in human spirituality.

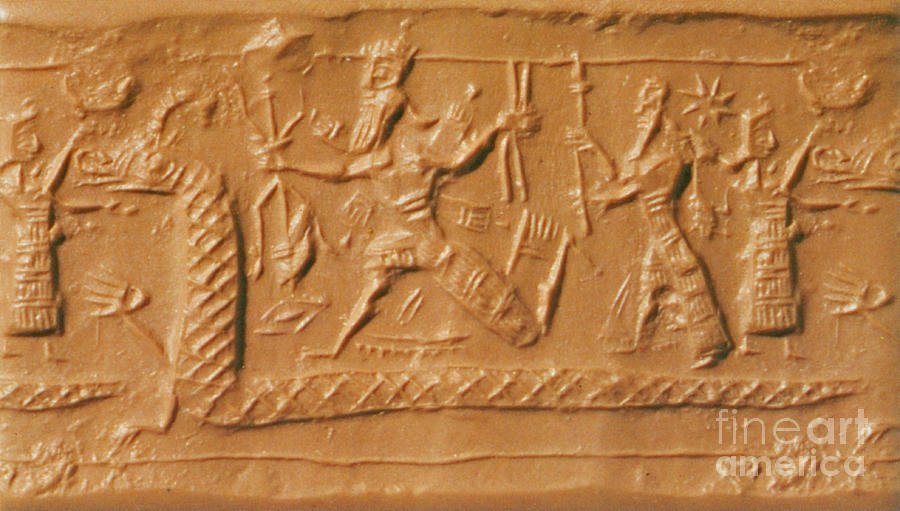

Battle Between Marduk And Tiamat Photograph by Photo Researchers

Transition in Mesopotamian Mythology: The Death of the Creator Goddess

In Mesopotamian mythology, particularly in the Babylonian creation myth known as the Enuma Elish (dating to around 1900 BCE), we witness a critical transition where the once honoured Creator Goddess, who had been central to earlier Sumerian myths, is displaced and even killed by the new masculine deity, Marduk. This myth is seen by some scholars as a pivotal moment in the shift from goddess-centred to patriarchal religion.

In the earlier Sumerian creation myth, the goddess Tiamat is a symbol of the primordial ocean, representing both chaos and creation. She was the mother of the first generation of gods, embodying both fertility and the creative force of the universe. Tiamat’s role as the creator links her directly to the feminine divine, as she embodies the power to birth and sustain life. She was revered as a source of life, as evidenced in the earlier Mesopotamian pantheon, where she was venerated as a goddess of creation and fertility.

As Babylonian mythology emerged, Marduk—the god of order, war, and masculinity—was introduced as a new deity whose ascension marked the shift toward the patriarchal dominance that would define later Babylonian religion. In the Enuma Elish, Marduk kills Tiamat in a violent confrontation, symbolizing the victory of order over chaos, but also the displacement of the feminine divine. After slaying Tiamat, Marduk cuts her in half, using her body to create the heavens and the earth, a direct claim to the creation powers that were once associated with the feminine principle.

The myth of Tiamat’s death is symbolic of the reduction of the goddess’s power and her transformation from a central figure of creation and fertility to a defeated force. This event marks a significant ideological shift, with Marduk claiming dominion over creation—a power that had previously been held by the Mother Goddess. This myth signifies the rise of the divine masculine and the appropriation of the earth’s fertility and life-giving abilities, which had traditionally been attributed to the feminine divine.

In the aftermath of Tiamat’s death, Marduk is exalted, and his role as the supreme deity leads to the patriarchal framing of creation. In this new paradigm, the masculine principle is credited with controlling creation and the forces of nature, while the goddess becomes a symbol of chaos and disorder, further diminishing her role in religious practices. This marks the beginning of the masculine divine claiming ownership of the very powers that were once associated with the divine feminine—a trend that would continue in the development of later monotheistic religions.

Bronze and Iron Ages

As societies became more complex and hierarchical, the worship of goddesses continued, though male deities began to emerge in parallel. Danu and Brigantia are notable examples of goddesses from Celtic traditions, representing fertility, sovereignty, and the land. However, in these societies, the divine feminine often took on more tribal and symbolic roles, reflecting the evolving balance between male and female powers in religious life.

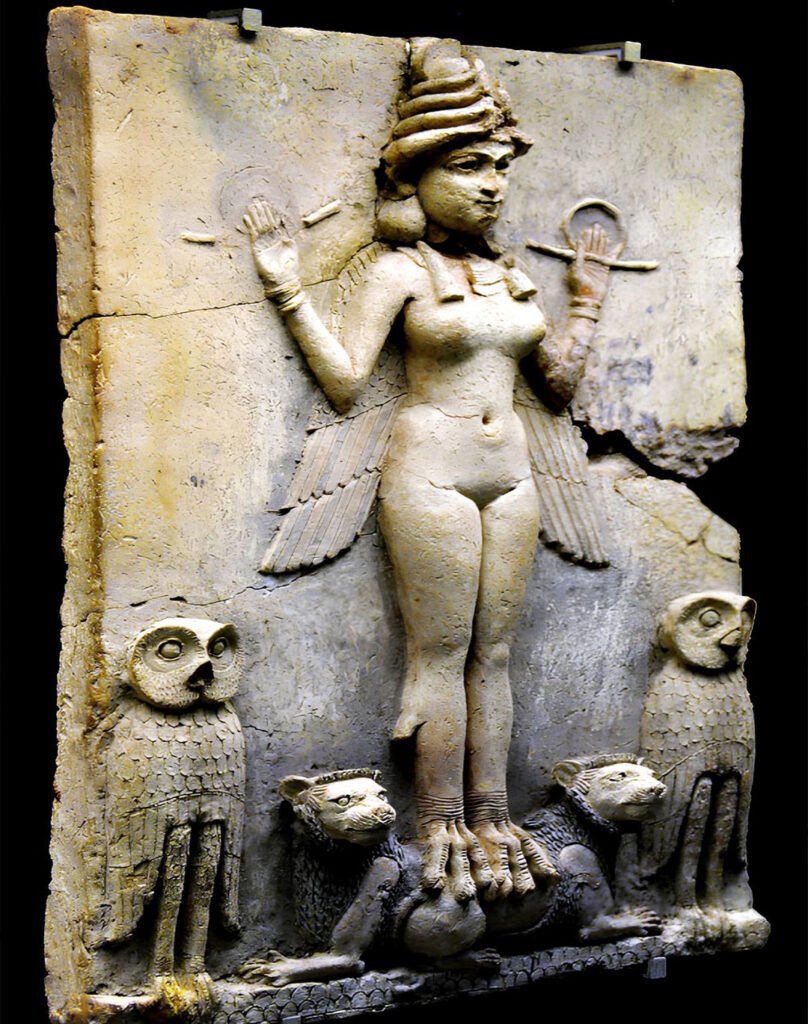

The Goddess Ishtar – Image by Pinterest

Classical Civilizations (Ancient Egypt, Greece, Rome)

In ancient Egypt, Isis and Hathor remained prominent goddesses representing love, fertility, and reproduction, while also embodying aspects of war and death. Egypt is a strong example of a culture where goddess worship remained vital even as patriarchal structures grew more prominent.

In Greece, deities like Demeter (goddess of the harvest) and Persephone (goddess of the underworld) represented a link between the earth’s fertility and the cycles of life and death. However, Greek mythology also saw the rise of male gods such as Zeus, whose influence overshadowed the divine feminine in many respects.

Roman Influence: By the time of the Roman Empire, feminine deities were often relegated to secondary roles behind their male counterparts. Venus, though celebrated as a goddess of love and fertility, was often overshadowed by more prominent male figures like Jupiter and Mars. As the Roman Empire expanded, the divine feminine was increasingly marginalized.

The Waning of the Divine Feminine

The further decline of the prominence of the divine feminine can also be attributed to the rise of monotheism and patriarchal systems:

Christianity and the Shift to Monotheism

With the spread of Christianity and the dominance of Abrahamic religions, the divine feminine faced significant repression. The Virgin Mary became the dominant female figure in Christianity, but her role was primarily one of purity and obedience, rather than a symbol of powerful feminine force. God the Father became the central, male figure in these religious traditions, and the goddess was no longer venerated in the way she had been in earlier polytheistic cultures.

The witch hunts and the persecution of pagan beliefs during the Middle Ages further marginalized the divine feminine, often associating women with witchcraft or evil in the eyes of the dominant male clergy.

Renaissance and Enlightenment

While some goddess figures appeared in mythology and art, the overall shift to rationalism and the rise of patriarchal states relegated the divine feminine to the margins. Feminine power was either depicted in mythological terms or suppressed through cultural and religious practices.

The Rise of Feminism and the Return of the Divine Feminine

The 20th century saw a significant reawakening of interest in the divine feminine, largely through the lens of feminism and women’s liberation. The second-wave feminist movement, in particular, encouraged a revaluation of gender roles and spiritual equality, leading to a renewed interest in the goddess as a symbol of empowerment and balance.

Women’s Liberation and the Recognition of Female Power

The 1970s and 1980s saw an explosion of women’s liberation movements that advocated for gender equality and female empowerment. The emphasis during this period was on practical action in achieving equal rights and opportunities. This era witnessed women’s advocacy for workplace rights, equal pay, reproductive rights, and freedom from gender-based discrimination, setting the stage for subsequent generations to continue challenging long-standing gender norms.

During this period, thinkers like Starhawk and Marija Gimbutas did bring attention to the prehistoric goddess cultures and the historical matriarchal systems, which laid a foundation for exploring ancient spiritual traditions. However, the focus of modern feminism has largely been about empowering women in the real world, with pragmatic actions in social, political, and professional spaces—without the need for a goddess archetype to symbolize this change. While the divine feminine has been an important part of some spiritual and feminist circles, the mainstream resurgence of women’s power is better reflected in their rise within secular domains, rather than in a return to mythological deities.

Contemporary Feminism and the Rise of Female Leaders

The resurgence of feminism in the 21st century is not solely about goddess spirituality or symbolic representations of the divine feminine. Instead, it is rooted in real-world progress for women, who are asserting their independence, leadership, and influence across all sectors. Today, we see female figures emerging as powerful role models in traditionally male-dominated fields such as business, science, politics, and even sports.

- Women like Angela Merkel, Jacinda Ardern, and Kamala Harris have shattered barriers in politics and leadership.

- In the business world, women such as Mary Barra (CEO of General Motors), Indra Nooyi (former CEO of PepsiCo), and Whitney Wolfe Herd (founder of Bumble) have achieved unparalleled success in top positions.

- In science, Marie Curie, Ada Lovelace, and more recently Katherine Johnson, Marie Maynard Daly, and Jane Goodall, have left a profound mark on their fields.

- In sports, Serena Williams, Megan Rapinoe, and others have risen to prominence, advocating for gender equality while achieving record-breaking feats in their respective fields.

Women today are changing the narrative not by invoking divine archetypes or resurrecting goddess symbolism, but through real achievements, social leadership, and cultural change. Their actions and successes are providing inspiration for future generations and challenging the patriarchal structures that have existed for centuries.

The Real-World Empowerment of Women

The divine feminine today is not simply about a spiritual return of some mystical divine feminine archetype, but rather about the empowerment of women through recognition of their equality and independence that has been enabled by the return of that zeitgeist in woman in general, regardless of their beliefs. This transformation is occurring in the real world, through women’s increasing presence in leadership roles, scientific achievement, and cultural shifts. The recent women’s movements are not focused on symbolic or spiritual reclamation of feminine power but on pragmatic change and progress.

By reshaping the gender dynamics in business, politics, sports, and more, women today are embodying the divine feminine through their agency, leadership, and resilience. This is a resurgence of feminine power that directly challenges the structures of patriarchy—not through spiritual symbols, but through the actions of real women. The Greenham Common protest, as we will explore, is one example of how women have claimed their power and challenged the structures that threatened their future, their children, and the world they inhabit. Their sacrifice and courage reflect a divine feminine that is now manifest through the women standing in the forefront of change.

However, the progress made by woman has been, and still is, not one without great hardship and sacrifice. In this article, I want to highlight some of those feminine heroes, and the sacrifices they made, and how they became the feminist heroines of their time. In order to do that, we need to go back to The Cold War….

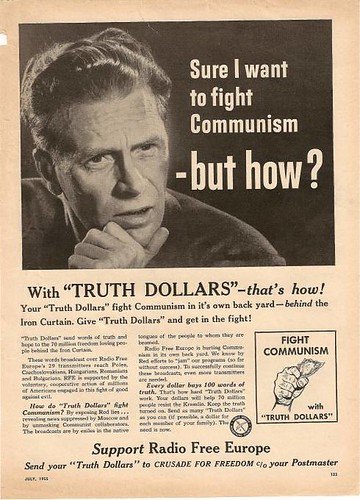

The Cold War, Greenham Common, and the Women’s Protest

The Cold War and the Fear of Nuclear War

The Cold War (c. 1947–1991) was marked by the intense geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. The two superpowers engaged in a nuclear arms race, each amassing vast arsenals of nuclear weapons. This period was defined by a constant fear of nuclear war, with the prospect of mutually assured destruction looming over global politics. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 brought the world to the brink of nuclear war, and throughout the Cold War, tensions between East and West were frequently high, with many feeling that a nuclear conflict was inevitable.

In the United Kingdom, the nuclear arms race took on a particular significance because of the presence of U.S. nuclear missiles stationed on British soil. Among the most prominent sites of concern was Greenham Common, located in Berkshire, which became the focal point for a decades-long protest against nuclear weapons.

Protesters from Greenham Common in the 1980’s

The Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp

The Greenham Common Peace Camp began in 1981 as a response to the decision by the British government to allow the United States to station Cruise missiles at Greenham Common Air Base. These missiles were part of NATO’s nuclear deterrence strategy during the Cold War, and their deployment was viewed by many as a direct threat to global peace. The fear of a nuclear war had a profound effect on society, especially on women, many of whom felt that their children’s future and the planet’s survival were at risk.

In September 1981, a group of women gathered outside the airbase in Greenham Common to protest the missile installations. They were not just protesting for peace, but also for a better future for the next generations. The protest grew into a long-term, nonviolent occupation by thousands of women, some of whom were mothers and grandmothers. The women formed the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, which would become an iconic symbol of feminist activism, resistance, and direct action.

The Protest: A Fight for the Future

The women at Greenham Common were not just protesting the missiles themselves, but the broader political landscape of fear and nuclear escalation. Many of the protesters felt that nuclear weapons were not just a threat to peace, but a symbol of patriarchal dominance and militarism. By protesting at Greenham, these women were challenging not just the military-industrial complex, but the gendered structures of power that kept women out of the conversation about security and war.

The protest at Greenham Common became one of the most significant acts of women’s activism in the 1980s, lasting for over 19 years. Women formed a physical barrier around the base, creating a peace camp where they lived and protested non-stop. This was an extraordinary display of women’s unity, strength, and commitment to peace, with women from all walks of life coming together for a common cause.

The Political and Social Climate

At the time, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the Reagan administration in the United States were firmly committed to the nuclear deterrence strategy. This made their stance on nuclear weapons particularly difficult to challenge. Thatcher, in particular, was seen as a staunch advocate of militarism, which further fuelled the resolve of the women at Greenham Common to stand against the installation of missiles and the militarization of society. The movement, however, was not just about nuclear weapons; it was about gendered power dynamics, the militarization of motherhood, and the agency of women in public political discourse.

Tactics and Actions

The women of Greenham Common employed a variety of tactics to gain attention, including:

Nonviolent direct action: Protests often included civil disobedience, such as blockades of military gates and the physical presence of women around the missile sites.

Chains and human barriers: Protesters created human chains and sometimes linked arms to form a symbolic barrier against nuclear escalation.

Symbolic acts of protest: Women performed rituals and ceremonial acts, including singing, chanting, and holding vigils, to emphasize the peaceful nature of the protest.

The Legacy of the Greenham Common Women’s Protest

Though the Greenham Common Peace Camp officially ended in 2000, its influence continued long after the protest itself had dissipated. The campaign had significant social and political impacts:

Shifting public perception: It helped raise awareness about the dangers of nuclear proliferation, and the role of women in the peace movement. The women of Greenham Common were crucial in creating a broader conversation about gender, peace, and disarmament.

Inspiring future movements: The protest helped shape later feminist and environmental movements, emphasizing the connection between militarism, gender, and the environment. It also paved the way for a growing recognition of the power of women-led activism in global politics.

Ultimately, the Greenham Common protest represents a heroic act of feminine resistance, where women stood for peace and justice, while challenging the status quo of male-dominated political and military systems. These women embodied a divine feminine power, one that rejected the violence and domination of the masculine principle and instead advocated for a world built on compassion, collaboration, and care for future generations.

The legacy of the Greenham Common women is part of a broader cultural shift towards the recognition of the feminine principle in modern times—not so much through a revival of goddess worship, but through the empowerment of real women who take action, fight for their rights, and refuse to remain silent in the face of injustice.

As we move into the next section, we will explore the modern-day heroes who carry this spirit forward, proving that the divine feminine is not just an ancient archetype but a living force that is shaping the world today.

The Divine Feminine on the Rise

The Changing Landscape for Women

As we look to the present day, we see a significant rise in female leadership across various sectors. Women are increasingly taking charge in areas that were once almost exclusively male-dominated, including politics, science, business, and sports. The divine feminine has found its expression not just in spiritual or symbolic terms, but in the real-world power that women are now claiming in everyday life.

This shift has been years in the making, driven by the feminist movements, the women’s liberation of the 20th century, and the fight for gender equality that continues today. But in recent decades, there has been a transformation—the idea of the divine feminine is no longer abstract; it is manifesting in women who are leading, creating, and transforming the world with their strength, intelligence, and vision.

Modern Feminist Heroines: Real-Life Embodiment of the Divine Feminine

The divine feminine is rising in women who demonstrate the same qualities of strength, leadership, and resilience that were once attributed to goddesses of fertility, war, and wisdom. These women are shaping history by leading nations, innovating industries, and challenging the status quo.

Politics

Jacinda Ardern, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, has been a global symbol of compassionate leadership. During her tenure, Ardern has led with a focus on inclusivity, gender equality, and social welfare, proving that strength and feminine qualities of empathy can coexist at the highest levels of leadership. Her handling of the Christchurch attacks and her efforts to combat climate change have made her a role model for women in politics worldwide.

Kamala Harris, the Vice President of the United States, made history as the first female, Black, and South Asian person to hold the office. Her rise to one of the highest political offices in the world is a testament to the changing tides and the growing recognition of women’s leadership on the global stage.

Business and Entrepreneurship

Mary Barra, the CEO of General Motors, is one of the most influential women in the automotive industry, a sector historically dominated by men. Barra’s leadership has brought innovation and a focus on sustainability to GM, making her an exemplar of how women can succeed in highly competitive fields.

Indra Nooyi, the former CEO of PepsiCo, is another powerful figure who reshaped the global business world with her visionary leadership and commitment to diversity and social responsibility. Nooyi broke down barriers in the business world, demonstrating how feminine qualities such as empathy, collaboration, and visionary thinking can be leveraged for business success.

Science and Technology

Marie Curie, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize, and Katherine Johnson, whose calculations were critical for the success of NASA’s early space missions, laid the groundwork for today’s women in STEM. The successes of women like Ada Lovelace and Rosalind Franklin in their respective fields have paved the way for future generations to thrive in science and technology.

Jane Goodall, whose ground-breaking work with chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream National Park revolutionized our understanding of primates, continues to be a beacon of scientific achievement and environmental activism. Goodall’s lifelong dedication to conservation and animal welfare highlights the compassionate leadership that defines the modern divine feminine.

Sports

Serena Williams, one of the greatest tennis players of all time, has become a symbol of strength, resilience, and dominance in the world of professional sports. Her unwavering drive, combined with her commitment to advocating for women’s rights, makes her a contemporary example of how the divine feminine is being manifested through athleticism, determination, and self-empowerment.

Megan Rapinoe, captain of the U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team, has been a fierce advocate for gender equality in sports. Her activism for equal pay and her outspoken stance on LGBTQ+ rights are key examples of how women in sports are using their platform to fight for social justice and equality on and off the field.

The Impact of These Heroines

The modern-day feminist heroines mentioned above are directly challenging the structures of patriarchy and rewriting the narrative of what it means to be a woman in positions of power. These women are redefining what it means to be powerful, successful, and resilient in traditionally male-dominated spaces.

Their achievements are a reflection of the growing recognition of women’s abilities across a range of domains. As these women rise to positions of influence, they are proving that the divine feminine is not just an abstract spiritual ideal, but a living, breathing force that continues to shape the world through the actions and achievements of real women.

The Resurgence of the Divine Feminine

The divine feminine is on the rise—not so much through spiritual movements or goddess worship, but through the real-world empowerment of women in leadership, science, business, and sports. Today, women are asserting their power and agency through positive action and real-world success, challenging the patriarchal structures that have long held them back. The Greenham Common protest remains a symbol of how the divine feminine fights for peace, justice, and the future of the planet.

As we have seen, these modern heroines embody the divine feminine—not as a relic of the past, but as a living force that continues to challenge, disrupt, and transform the world. The sacrifices and actions of these women—whether on the battlefield of politics, business, sports, or science—are paving the way for future generations to flourish and thrive in a more equal and empowered world.

Subscribe to our post updates - Don't miss a thing!!